Field Research: Day 30

A month after my Permanent Change of Station to America, I visited a restaurant called Chipotle Mexican Grill. During the ordering process, I pointed to one of the optional condiments and asked, “Is that some sort of garlic sauce?” The young burrito roller looked at me through the dirty glass and mumbled, “That’s sour cream.” Something in his confused reaction and slack-jawed cadence made it very clear that this establishment would require extensive further research. I returned home and submitted a job application on chipotle.com. After my second interview, the restaurant manager gleefully announced, “Congratulations! We have decided that you have all the thirteen traits needed to work at Chipotle!”

To professionally partake in Chipotlean eudaemonia, a job seeker must attain thirteen Confucius-inspired virtues: conscientiousness, respectfulness, hospitality, highness of energy, infectiousness of enthusiasm, happiness, presentability, intelligence, politeness, motivation, ambitiousness, curiosity and honesty.

I walked through the crisp January air and arrived at 07:50AM on my first day of work. I knocked on the cold glass door and an uncertain figure looked up from lazily mopping the floor. She walked over to let me in. The restaurant manager gathered everyone for a quick pow-wow and announced, “David (not his real name) will not be working here anymore, because of inappropriate behavior. We have to be respectful and supportive of each other.”

I was asked to dice a crate of red onions and a woman from Montana instructed me on the proper Chipotle dicing method. She was in her early twenties and told me that she had just given birth. “I got married right after high-school,” she told me, “but I never saw myself as that kind of person. You know, the kind that gets married right after high-school.”

The Montana woman closely monitored my work as I diced the onions. Shape and size — internally called “cut sizes” — are deemed very important. She studied my work and repeated, “Consistent cut sizes are very, very important.”

Someone plugged a phone into the speaker system and brutal death metal poured into the room. The Montana girl — yelling over the music — explained that her husband was a pastor and that they had spent a year in China doing undercover missionary work. I told her that before America, I had been permanently stationed in China for about seven years. We traded some basic stories of life in China. Overall, the Montana woman was very pleasant.

Those first hours of my first day were peppered with talk of food safety. This was early January, 2016, and I soon learned that this was the peak of Chipotle’s food safety concerns. The chain had in recent memory caused a hepatitis A outbreak, and then a norovirus outbreak, and then a Campylobacter jejuni outbreak, and then an E. coli outbreak, and then a second norovirus outbreak, and then a Salmonella outbreak, and then a second E. coli outbreak, and then a third E. coli outbreak, and then, finally, a third norovirus outbreak. The National Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimated that approximately 5,000 people in 19 states had gotten sick from Chipotle’s food.

The location I worked at—in the Seattle’s University District—had been implicated in its very own E. coli outbreak. My fellow employees told me how much they hated that week, “We had to close the restaurant and bleach everything. They even made us unscrew the handles from the rice cookers and bleach under the handles. It wasn’t fun.”

I finished dicing red onions and moved onto shredding romaine lettuce. The restaurant manager hovered behind me, incessantly repeating, “Food safety is number one right now. We have to focus on food safety.” A moment later she returned and told me, “Your cut sizes are off. You are wasting too much.” She reached down into the trash can and — digging through the miscellaneous waste of floor dirt and used rubber gloves — extracted the romaine that I had just discarded. My eyebrows shot up in surprise and she began acting defensive and nervous. “It is fine,” she said, “We’ll rinse the lettuce afterwards.”

She then placed my previously rejected piece of lettuce stalk on the cutting board and showed me how to cut close around the stem to get a tiny bit more lettuce out of each head. She added these new shreds to the large hotel pan of lettuce that we were about to serve to our customers. At that moment, an alarm rang, indicating that all staff should wash their hands. Someone said, “Yeah, we’re supposed to wash our hands now, but we are in the middle of this task so we’ll skip it this time.”

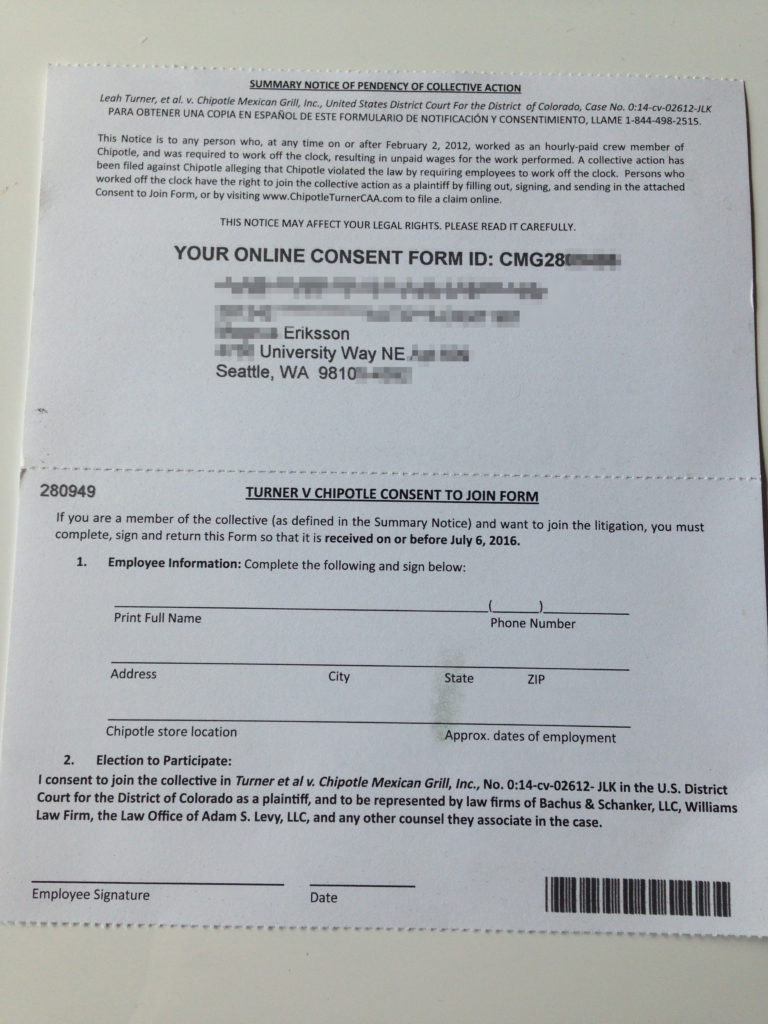

I looked around. Wall posters explained what part of an onion or avocado we were allowed to throw away. Our focus on food safety was competing with a focus on minimizing waste and time management. The restaurant manager showed me a schedule on the wall and said, “This is called the Daily Deployment.” This chart outlined how many minutes we could spend on any given task. “Green Tomatillo”, 23 minutes. “Cut Citrus”, 10 minutes. These weekly charts also showed an allowed aggregate number of hours and minutes of labor for each day. At the bottom of the paper, these numbers were compared to a recommended number of hours based on projected sales. From a business point of view, this is all very sensible. At the same time, it is true that Chipotle probable has a problem with a runaway focus on labor costs, because—allegedly—a lot of Chipotle managers pressure employees to finish their tasks “off the clock.” Which is against the law. Personally, I never witnessed anyone being pressured into unpaid labor, but in the fall of 2016 the Chipotle corporation became embroiled in a 10,000-employee-strong class action lawsuit pertaining to these illicit practices.

When discussing this issue with a random sample of American civilians on the street, it is clear how this can happen. The Americans do not recognize the culpability of the employee. In America, all individuals focus on doing whatever it takes to curry favor with their immediate superiors. They are happy to break the law and work off the clock if that means possibly getting promoted. In Sweden, we are very concerned with the big picture: If we disregard labor law (working off the clock, not asking for overtime pay, not asking for legally mandated Paid Time Off, disregarding allowed paid paternal leave, disregarding work/life balance), then companies who follow the law will not be able to compete. Everyone will be forced into the same state of misery and chronic over-work. American careerists work longer hours than most people in the developed world. Please note that they brought this upon themselves.

We finished shredding the romaine lettuce and poured the green chunks into a sink and soaked them in VictoryWash™. This is a milky liquid so poisonous that all employees have to wear safety goggles while handling the soaked lettuce. At the same time, this substance is so harmless that it is considered safe to leave some on the lettuce for customers to consume. This is somewhat counter-intuitive, but as a Swedish person I have a well-documented trust in science and established institutions. When discussing these washing practices with a random sample of American civilians, more cultural differences become apparent. A representative conversation proceeds along these lines:

Swedish Person: “Why would Chipotle want to poison its own customers? A large corporation has long-term goals—brand management and not poisoning your customer base.”

American Person: “If the customers develops cancer ten years after eating that burrito, then there is no way to prove that it was because of Chipotle.”

Swedish Person: “But the government regulators have surely tested these chemicals. There is surely a scientific explanation.”

American Person: “These chemicals are probably illegal in Europe.”

After lunch I spent about an hour cutting bell peppers into identical strips and then someone yelled, “Joakim, we need you in the dish pit!” I sidled up next to a nineteen-year-old boy with scruffy facial hair and pimples. While using a high-pressure water gun to spray salsa and dried beans off the pots and pans, he told me his life story, “Heavy metal is everything to me. Me and my band mates are very serious about what we do. I play the guitar. I will move down to Tacoma next week because the rest of the band is based there.”

His long hair bounced against the large frame of his glasses as he vigorously scrubbed at the dried salsa. He asked a lot of questions but never waited for me to answer. “What do you like to do in your spare time? Do you ever do drugs? Did you ever do psychedelics? Like hardcore psychedelics?”

He told me about his daily weed smoking regimen and then tried to convince me to buy some of his magic mushrooms. In the middle of a very animated sales pitch, I was distracted by a voice coming from around the corner. It was a gentle, mature voice. It said, “Oh, just a regular visit, nothing special, just a little visit…”

I thought to myself, “What does that mean?”

One of the middle-managers entered the dish pit and crept up next to me. He pretended like he was washing dishes and whispered with a hissing voice, “OK. So the health department is here.” Struggling to act normal, he nervously repeated, “OK. The health department is here. Act cool.”

The restaurant manager burst into the dish pit — her panicked eyes darting back and forth. She stuck her hands in our three sinks and shrieked, “Why is the sanitizer above seventy degrees? Why is the sanitizer above seventy degrees?” She looked at me. I did not speak. I tried to telepathically communicate the following: “Calm down. I don’t know what you are talking about. This is my first day. I don’t know anything about sanitizer temperature.”

She then looked over at my young drug-dealer companion and he shrugged sheepishly. She frantically started draining the water from the sanitizer sink — refilling it with cooler water. After this, she left and quickly returned with all the restaurant’s knives. She handed them to us and told us to clean them. Having closely studied the entire employee handbook on the previous day, I knew that this was a blatant breach of safety policy. Knives are never to be handed between two people. There are knife safety and food safety reasons for this. I decided that this was not the time to point this out.

My young drug-dealer companion and I used fresh steel wool to wash the knives. And that was when I saw him: The Health Inspector. He was an old man. A small man. Barely five feet tall. He had white hair and a chinstrap beard, like an old sea captain. He was blinking at us with innocent grey eyes. He smiled at me. I smiled back. There was something beautiful in that moment. I immediately knew that there was something very curious — almost inexplicable — about him. He did not utter a word, instead he trotted on. In a flash he was gone and I never saw him again. In my mind, he quickly morphed into a sort of tomte — a creature from Scandinavian folklore, denoting a protective spirit of the farmstead, usually imagined similar to a garden gnome. The tomte takes care of the cattle and the crops. He scurries through the snow to make sure that the barn is locked at night. Belief in a tomte is a form of ancestral worship, because he is viewed as the man who first cleared the forest and built the farmstead. The tomte wants to make sure that everyone is cared for. This was the Health Inspector. He built this restaurant, and now he wanted to protect everyone from salmonella.

The restaurant manager came back into the dish pit and told us that our restaurant had passed the inspection. She let out a sigh of relief and said, “He is actually a very nice man.”

4 replies on “What I Learned After Moving To America And Getting a Job at Chipotle (part1)”

as I was reading this I started to get so hungry for a burrito.

Joakim.

If a restaurant does not meet the required hygene standards, what are the consequences for that restaurant? As you know, here in Sweden, all visits by health inspectors follow advanced warning and the General public are nearly never informed of the results.

In late 2016, King County (where I live) rolled out a new system for presenting this information to the public. Conspicuous posters are now posted in all restaurants. There are four grades: Needs to improve, Okay, Good, Excellent.

http://www.kingcounty.gov/depts/health/environmental-health/food-safety/~/media/depts/health/environmental-health/images/food-safety/food-safety-rating-poster-explained.ashx

This is (of course) based on a model that has been used for many years in the municipality of Shanghai. There, it is a three-grade system: 良好 Excellent, 一般 Pass, 较差 Fail.

http://shanghai.cfsn.cn/locality/shanghai/img/attachement/jpg/site2/20130420/081076ee1a9b12dc91c70c.jpg

This is a brave new century, where the Americans are constantly copying the Chinese.

This article has gotten me hooked on your website!

And yeah, I always thought that America was somewhat oddball vis-a-vis the rest of the West.

Apparently, perhaps thanks to the environment in which this country (USA) developed, one of our primary cultures, cowboy culture, ended up being sorta like those of the various Eurasian steppe nomads, like the Scythians, the Huns, and the Mongols:

http://theplate.nationalgeographic.com/2015/09/17/going-home-home-on-the-steppes-of-eurasia/

http://www.horsenomads.info/introduction.html

The last link states that “the frequently brutal harshness of trying to make a day-to-day living on the steppe forged a people who were fundamentally tough, resilient, and self-reliant—precisely the traits of the successful warrior.” This might partly explain why America has been reluctant to buy into the idea of the European-style social democracy.