Field Research: Day 391

Today I went to the Varsity Theater in Seattle and paid $4.00 for a bag of peanut M&Ms and $10.50 for a ticket to Birth of a Nation. The girl at the concession counter gave me the ticket stub and said, “It is in number two. I don’t know what it says up there. But it’s in number two.” I walked up two flights of stairs and looked at the signs:

Auditorium #1: The Birth of a Nation

Auditorium #2: The Girl on a Train

“Ah, she meant that the signs were wrong,” I told myself. I walked passed the homeless man standing in the middle of the hallway—his body slowly swaying back and forth—and entered Auditorium 2. The room was empty and well-lit. I sat down. The screen was off but the sound was on. I listened to the deafening roar of commercials and watched the blank screen. Then I listened to the loud and incomprehensible audio track of a series of previews and kept my eyes nailed to the blank screen.

“I’m sure they’ll turn the screen on when the movie starts,” I thought to myself. After another couple of minutes, I heard the sound of hooves and a child breathing. I heard the sound of a person running through a forest. The screen was still dark.

“Has the movie started?” I asked myself, “What is happening here?”

I stood up and walked into the other auditorium. That screen was off too. The homeless man was sleeping across four or five seats in the first row. Then I saw him: a young man with a backpack. He was the only other paying patron in the building.

“Are you also here to see the Birth of a Nation?” he asked.

“Yes,” I responded, “But it seems like they have forgotten to turn the screen on.”

I walked downstairs to the concession counter and explained to the girl that the screen was off. She walked passed me and mumbled, “Right, I forgot to turn it on.”

I sat back down in auditorium 2 and, to my dismay, the movie did not start from the beginning. I missed the first ten minutes.

This Based-on-a-True-Story historical drama revolves around young slave Nat Turner. He lives in a wooden hut. He speaks to the candle-lit face of his grandmother. We join the story just after this young boy’s plantation-dwelling father has killed a white man. Nat begs his father not to leave. The boy gets a formulaic “you are the man of the house now” response from his father. The boy cries. We are clearly meant to understand that this is a formative moment in the life of young Nat Turner.

I crack open a can of La Croix. The cold pamplemousse burns beautifully in my parched throat. One thing is already clear: This isn’t a very good movie. The acting is uninspired. The camera work is conventional and flat. Somehow, the plot is very simple and still very confusing. Most of the actors have bad teeth, but that is the full extent of the movie’s historical accuracy. The plot does, however, brush up against interesting themes. For example, Nat Turner (now in his twenties) falls in love with another slave and marries her. Were love marriages between slaves common in the Antebellum South? What did that look like? Did slaves have any agency? None of these questions are explored. Instead, slave Nat Turner exchanges lustful glances with another slave and then the next scene is a marriage scene. No details. After a period of martial bliss, his slave master hosts a dinner party and one of the guests wants to sleep with Nat Turner’s wife. Arguing ensues. The wife is taken away so that the dinner guest can rape her. Nat Turner has a meltdown and in that moment, he decides to incite the slave rebellion that made him famous. Before this point, the plot has stayed close to real historical accounts of Nat Turner’s life. But the rape and its triggering role in his life is fictional.

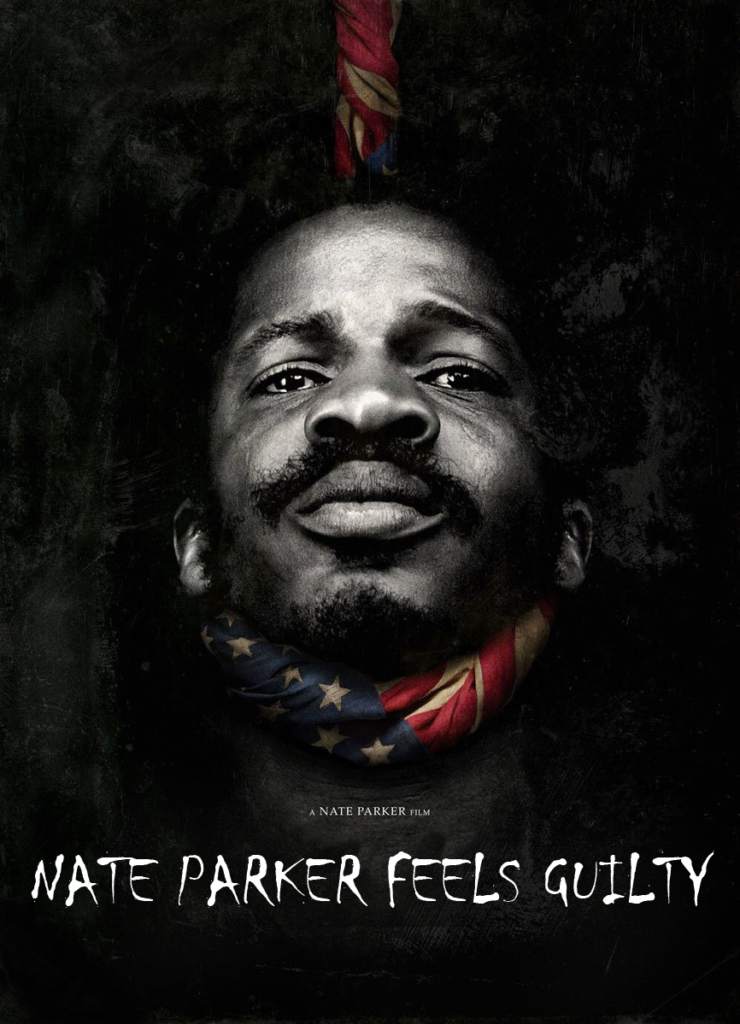

At this point, we have to talk about Nate Parker, the director, writer, and main actor of the movie, and how he was famously accused of rape.

In 1999, while a sophomore at Pennsylvania State University, Parker and his roommate and wrestling teammate, Jean McGianni Celestin, were accused of raping a fellow student. The unnamed accuser stated that Parker and Celestin raped her while she was intoxicated and unconscious, and that she was unsure of how many people had been involved. The woman later went to a doctor, who concluded that she had been sexually assaulted, and local authorities taped a phone conversation between her and Parker in which Parker confirmed that it was he and Celestin who had sex with her. She also stated that the two harassed her after she pressed charges, and that they hired a private investigator who showed her picture around campus, revealing her identity.

In other words, we know that Nate Parker gang-raped a woman in college. But he was was “acquitted on all four counts.” He got away with it. A miscarriage of justice. Then, in 2012, the victim (a reportedly very haunted young woman) committed suicide. In 2013, Nate Parker told his agents “he would not continue acting until he had played Nat Turner in a film.” So he proceeds to write a screenplay about slave rebellion hero Nat Turner. He invents a rape scene and decides to make it the triggering event for the entire slave rebellion. (Again, historical accounts do not mention rape). Then Nate Parker goes trolling around for financing and somehow he acquires funding and actually makes this turdburger of a movie.

Can we please have an honest conversation about this? Can we please acknowledge what is happening here? Nate Parker is consumed by guilt. He is a Raskolnikov-type character[1]. He is a perfect Freudian case study. He probably doesn’t know why he is doing any of this. But this is about alleviating guilt. His subconscious was probably hoping that in the process of making this movie and casting himself as the hero, he would feel better. Think of the size of this project and how it is all just Freudian projection. He writes an entire screenplay and acquires $8.5 million of funding and gets all these people together—cameramen, actors, publicists, the people who make the little sandwiches—all of it just so that Nate Parker can perhaps feel better. And then he acts it all out. A woman comes out of the slave master’s mansion. It is clear that she has been raped. Nate Parker falls to his knees in the mud. Rain whips at his face. His slave master beats him. Nate Parker wants nothing more than to be punished for what he did. Nate Parker wants someone to yell at him and tell him that he is a horrible human being. Nate Parker doesn’t know why he can’t sleep at night. Nate Parker doesn’t understand what is happening. The woman who plays his wife (Aja Naomi King, bless her heart, imagine getting caught up in someone else’s Freudian fever-dream) is crying. Her dress is torn. This scene is set in the early morning. The vague pre-dawn light gives her an eerie presence. She is beautiful. Nate Parker as Nat Turner[2] looks at Aja Naomi King as Cherry Turner and he starts crying, bawling. He loses it. He rips his hair out. Nate Parker cries because he is entitled and he wants Hollywood forgiveness. He wants to spend $8.5 million so that maybe he can feel better. This is Shakespearean. This is classical Greek Antiquity tragicomedy. This is all of that rolled into one.

The best and worst part of this meta-event is that Nate Parker—to this day—doesn’t know why he made this movie. Not that people haven’t suggested it to him. I mean, he was interviewed by 60 Minutes and they asked him if it had anything to do with guilt. He said no.

We are roughly ninety minutes into the movie (Nat Turner has just finished organizing his fellow slaves for the rebellion and he decides to start by killing his own slave master–hacking him to death with a small axe) and then the screen freezes.

“I guess this movie viewing experience is over for me,” my mind quips cheerily to my heart. I look over at my fellow traveler a few rows down. The backpack on his lap. He starts complaining, “I hate digital cinema. Stuff like this always happens.”

I don’t know anything about digital cinema, so I walk downstairs to find concession girl so that she can turn the movie back on. The building is now empty.

“This is a ghost theater,” says my sad compatriot. Because he has a strong sense of drama. He surrenders and walks home. I decide to explore the theater, since none of the doors are locked. I walk through a dark hallway full of cables. I cross an open space, dark and scary, and arrive at another hallway. I stumble into a dark room where the concession girl is watching Glee on her laptop. I pretend like I have been looking for her, saying, “Oh, there you are, I was just looking for you.”

Then I say, “The movie isn’t working.”

“Oh? Really?” she responds, “I was just up there, like two minutes ago, I just checked on it.”

She can’t get it working, so instead she gives me two free tickets and sends me on my way. So overall, I would give this movie two out of five Coat of Arms of Sweden.

[1] Well, you know, there’s this little Russian novel called Crime and Punishment, written by Fyodor Dostoyevsky, and in that book the protagonist feels really guilty.

[2] Also, we need to acknowledge that Nat Turner and Nate Parker are very similar names. I am sure that Sigmund Freud’s Die Traumdeutung has a chapter on how you might end up acting in a play within a play with a historical character with a name similar to your own—because the subconscious a curious apparatus.

2 replies on “Movie Review: Birth of a Nation (2016)”

You know, I wonder what the girl thought about all of this. Living the American dream

Livin’ the nightmare