Field Research: Day 1

“Shifu, today I am moving to America,” I say as the taxi climbs the on-ramp and careens toward the Beijing Capital Airport. At first, the taxi driver does not respond. Then he mumbles, “Good.”

We do not speak for the rest of the car ride. Instead, I peer out through the unwashed backseat window. The Beijing suburbs are draped in air pollution, as if we are watching the present through the fog of recollection. We pull up at terminal 2 and—as I carefully remove my research equipment from the trunk of the taxi—I ask myself, “Why did I just spend seven years in China?”

Like my mother always said: “Sju svåra år.”[3]

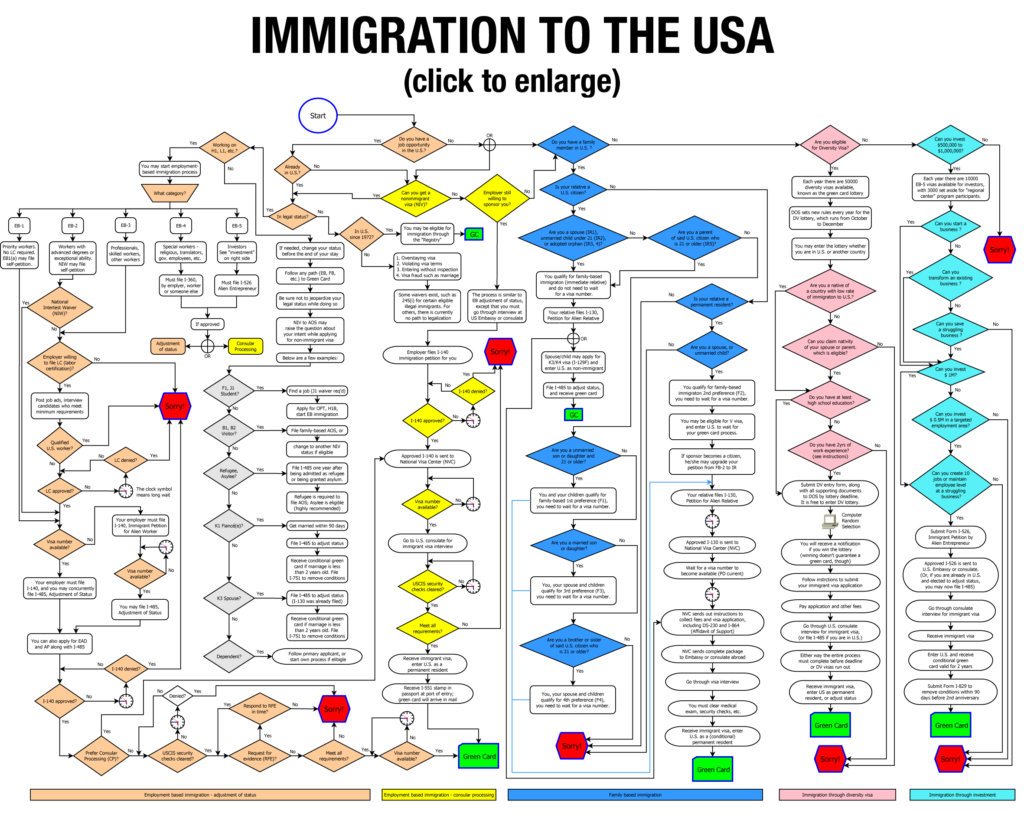

Fifteen hours later I step off the plane at the Seattle Tacoma Airport. I stand in the Area 2 immigration line with my large manila folder of approved visa documentation. I worry that my sweaty palms will dissolve the glue of the sealed envelope.

In my head, I prepare an elaborate defense.

I apologize, officer. I did not intentionally open this package, officer. I have spent the last five weeks caring for this package as if it was my firstborn child, officer. I have protected it against a series of rambunctious house parties at our Beijing research facilities and, in fact, it was fully sealed until a minute ago when I arrived at the back of this visa line. Unbeknownst to me, the heat and moisture of my palms seem to have dissolved the glue, sir.

I notice that the immigration officer serving my queue is a woman, and I cannot remember how to address female officers. I don’t think I can pull off saying “mam.” I decide to get in another line. Eventually, I am called over to a counter and the officer casually disregards the three ceremonious red stamps of my envelope. He dumps the content on his desk and gestures toward a uniformed female behind him, saying, “Follow this nice lady to the waiting area.”

She laughs and they proceed to candidly flirt as we walk away. Somehow, I find it calming that they have no sense of shame. I take a seat next to an African woman with four small children. All the other people in the waiting area are Chinese or middle-eastern. After a few minutes, a new immigration officer loudly mispronounces my name into the microphone and I rise for the occasion. He asks me to state my name and my birthday. Then he says, “Victims of domestic violence are, under all circumstances, protected under the law. This includes physical, sexual and economic violence. You may seek help regardless of your immigration status. You are here on a CR1 visa—”

I interrupt him to say, “CR stands for conditional relationship. That’s because my wife and I have been married for less than a year.”

I say this because I want him to know that I am listening and that I understand what he is saying. I want to seem like a reasonable person that you would want to allow into your country. He looks at me and his face slowly melts into frown. A moment passes without either of us speaking. I realize that this is not a conversation. He is reading my rights. I should not cut him off. His eyes narrow to a squint and he considers throwing me in immigration jail for interrupting. Then he shakes it off and says, “As I was saying…”

IN CONVERSATION WITH GOVERNMENT

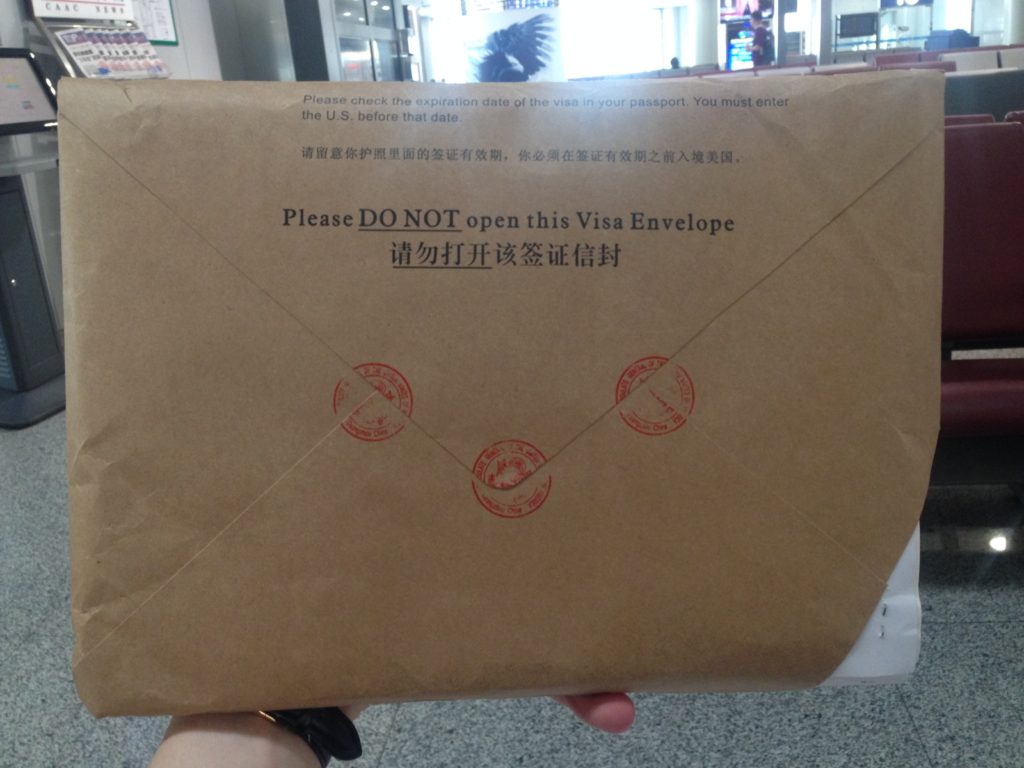

The bureaucratic path that brought me to this immigration waiting area was mysterious and grueling. We submitted stack after stack of paperwork. Our final petition was, including all appendices, approximately 200 pages. This process culminated in an in-person interview at the US consulate in Guangzhou. To a Swede, this is all very exotic. We, the Swedes, are fully accustomed to being frustrated with the speed of government action and we often disagree with government decisions. But interactions with the Swedish government are mostly transparent, agreeable and clear. This is because the Swedish government has adopted a language-political objective of “Klarspråk”—clarity of language. Even a person of below average faculties should be able to understand all communications from the government. Bewildering paperwork is widely perceived as a failure of government. A notable example was the 2002 horror story of the “Impossible to Understand Letter” sent to all retirees by the Swedish Social Insurance Agency. This letter—written in impenetrable legalese with several references to statutory paragraphs—prompted hundreds of complaint calls. A multi-department investigation was conducted to revolutionize the agency’s work process.

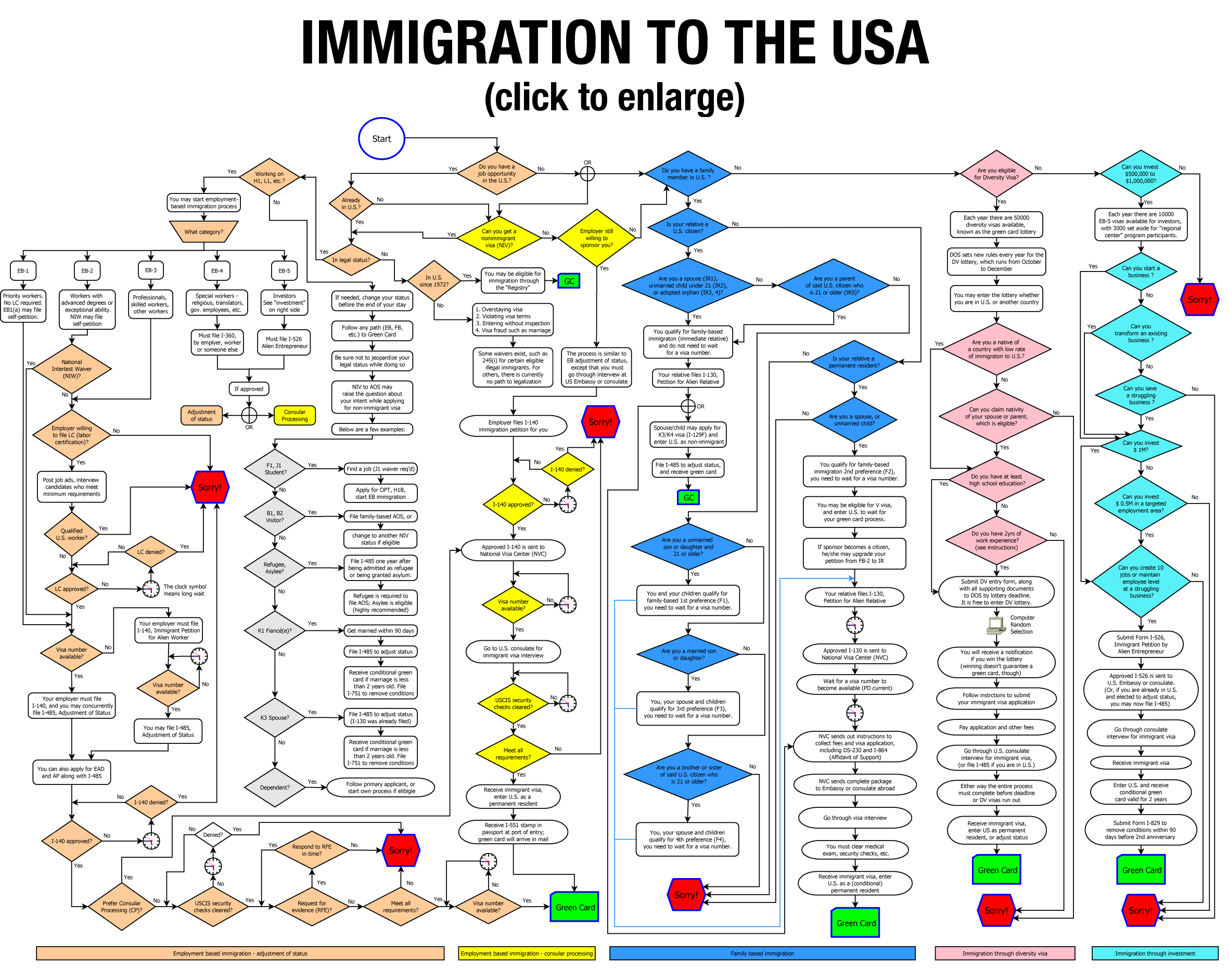

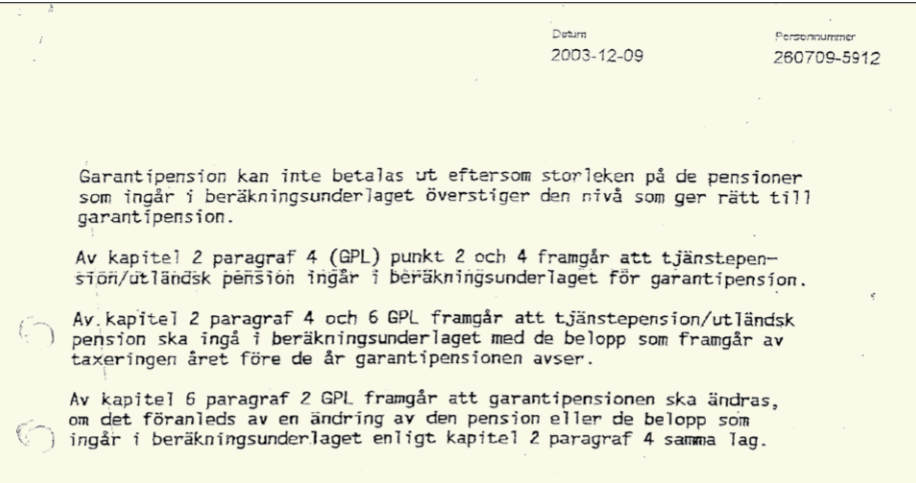

In America, the government will happily shift the Burden of Comprehensibility onto the individual. It is not perceived as a failure that a person of average faculties will need fifty hours of studying before even attempting to fill out the first immigration form, or that any immigration applicant must memorize the names of all relevant forms: the I-130, the I-90 and the I-131A. If you fail this test of comprehension and memorization, you need to hire a lawyer. To a Swede, it is absurd that you would need a lawyer to interact with your government.

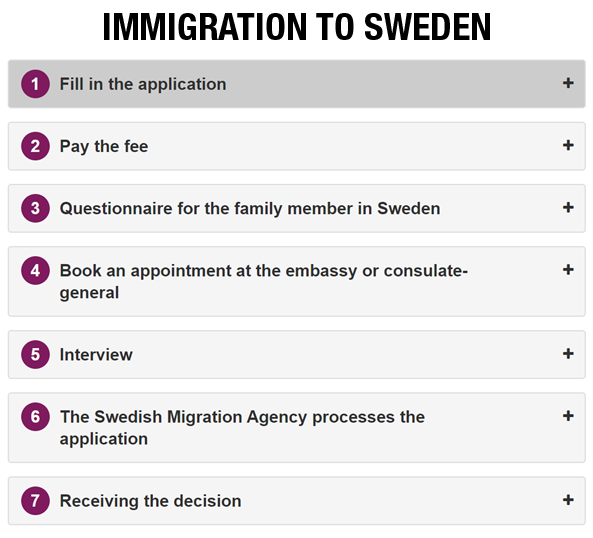

To further illustrate this point, consider the following flow-charts.

“Are you even listening?” asks the immigration officer and I snap back to reality.

“Yes, of course,” I respond, “I will receive my green card in the mail. That’s what you said, right?”

“Right.”

EMERALD TOWN, USA

As our Uber car drives through Seattle, I am struck by how small everything feels. Most neighborhoods are lined with two-story buildings and most storefronts are dark and unexciting. I had expected Seattle to be a World City. A Global City. Our car turns onto our street in the University District. Coming from China, where fifteen million people can reside in a city you’ve never heard of, I get the distinct feeling that Seattle is a ‘town’. But the role of the high-rise building interests me, because it relates to differing conceptions of “downtown.” In China, you are always surrounded by high-rises, regardless of being downtown or not. In Sweden, you are never surrounded by high-rises, but we still conceive of a “downtown.” In Seattle, ‘downtown’ is defined as the small cluster of high-rises in the middle of the city. I have never before seen a more clearly delimited ‘downtown’.

I put my bags down and check to see if any research equipment was damaged during transit. Everything looks good, so I exit our building. I walk around the corner and see a gas station with a blinking sign that says ATM. I walk inside and cheerily ask, “Hi there, do you guys have an ATM here?”

The clerk flashes a disgruntled look and gestures for me to go away. I find the ATM on my own and withdraw some army-green bills. I think to myself.

So this is where I live now. This is my gas station. Sure, we don’t have a car and I don’t have a driver’s license. But this is my gas station. This is where I’ll buy milk late at night after the grocery store has closed. This is where I’ll buy Swedish fish when I am too tired to go anywhere else. And sometimes when I’m feeling lonely, I’ll just saunter in here for now reason and strike up a conversation with the clerk. Eventually, I will probably find out why she sometimes looks so disgruntled. This is the first set piece of my new life—my gas station.

During the next nine months of living on that street, I never go back into that gas station. Instead, I walk around the corner and find a large 24-hour grocery store with self-checkout robots.

[1] “师傅,今天我搬到美国”

[2] “好”

[3] Ewa Eriksson, Quotations from Mamma Ewa Eriksson, (Höörs kommun, 2002): “Seven years of famine.”